Seattle transformed by underground highway 23 Jan 2020

After eight years of construction and a US$3.4 billion public investment, the State highway SR99 tunnel has forever transformed the Seattle waterfront. Customers at a sidewalk food stand along the waterfront no longer compete against the 80-decibel roar of the double-decked Alaskan Way viaduct that the tunnel replaced. The din moved underground and is trapped within the two miles of segmental lining left behind by the mega TBM of 17.4m diameter. “With the viaduct down, it is a lot less messy,” said food stand proprietor Shanah Wheeler on a winter Sunday afternoon. “It is a lot brighter and people notice us a lot more.”

Fueled by cruise-ship growth, tourism to downtown Seattle was already breaking records in the 2010s despite endless construction clatter from the SR99 tunnel excavation works and replacement of the seawall along the waterfront. Demolition of the double deck highway viaduct in 2019 became a good reason to ride the Seattle ferris-wheel which affords panoramic views of the before-and-after perspectives of the waterfront.

To some longtime Seattle residents, the new highway tunnel reflects a city drowning in big money. Working people realize the tunnel created windfall profits for owners of nouveau-view properties. Some $7 billion in land deals occurred last decade near the shore, a Seattle Times newspaper analysis found. Land barons can thank drivers who pay gasoline tax. In funding the tunnel, motorists lost their own views, from the viaduct of Puget Sound and the Olympic Mountains. “In general, they want the whole city to look like an Amazon campus,” said one resident. “The viaduct was gritty. It was dark, it was gritty Seattle.”

As an underground traffic highway, the tunnel has excelled since it opened on 4 February 2019. Despite fewer on and off ramps than the former viaduct, the four-lane, double-deck tunnel carries 75,000 daily vehicles and a feared breakdown in freight movement has not materialized. But toll charges, ranging from $1 to $2.25, imposed in November 2019, have sent more than a quarter of those drivers back to surface streets, undermining the role of the tunnel in reviving the waterfront. Tolls were demanded by State lawmakers outside Seattle to lubricate a political deal in 2009 to adopt the bored tunnel option for the SR99 viaduct replacement.

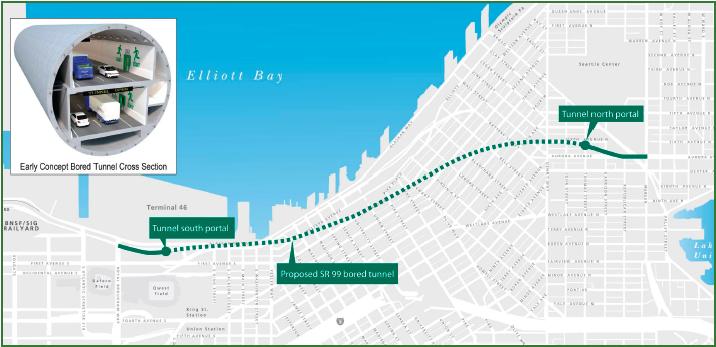

The impetus for the project was an earthquake in 2001 that caused the viaduct, built in 1953, to crack and settle, requiring a purportedly urgent replacement. Washington State burned through $300 million and eight years for public outreach, technical consulting, and environmental study fees before Governor Chris Gregoire chose a single-bore tunnel.

Except for debunking bad alternatives, including a wider replacement viaduct, that outlay did not inform the tunnel engineering, save for the hundreds of soil samples that gave tunnel contractors Seattle Tunnel Partners (STP) and TBM manufacturer Hitachi Zosen an indication of the ground through which the tunnel would be excavated. As TunnelTalk readers know, the mega-TBM stalled in the soggy, waterlogged fill soils and required a repair operation that delayed the project by two years, a situation that STP blames on a steel groundwater investigation casing.

The STP partners, Dragados and Tutor-Perini, lost their court case claim for $330 million to cover the costs associated with the two-year TBM breakdown and its unprecedented repair mission. Appeals are now pending and could linger for years.

It should be noted that post-repair, the machine turned inland to bore capably through firm glacial till and clays in the downtown hillside, 200ft deep, without sinkholes or surface settlement, a feat not achieved by smaller diameter transit and sewer TBM drives.

But owner of the project, the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), is not handing out dollars for sweat equity. Project managers and attorneys assert contractor mistakes, such as poor soil conditioning, caused the TBM breakdown. For WSDOT, which won a $57 million court case award, the case was about failure by STP to meet contract obligations to finish the project on time.

WSDOT had already sweetened the deal in 2011, when signing the $1.44 billion design-build contract. Design-build passes more risk to the contractors but pays more upfront. Late in procurement, WSDOT tacked on a $230 million risk allowance to the civil works estimate of $1.1 billion.

But what is the future for TBMs after Seattle set a world record size at 17.4m diameter? Will TBMs keep growing in size? For underground construction engineers who seek to push the limits, Seattle proved a 57ft diameter TBM excavation is feasible and perhaps greater is possible in better soils than under Seattle. However, the TunnelTalk table of mega TBMs shows that only one of the latest 27 mega-TBMs surpasses the size of the machine that excavated the SR99 highway tunnel that has forever transformed the waterfront in the city of Seattle.

Contributed to TunnelTalk by Mike Lindblom, reporter with The Seattle Times

(mlindblom@seattletimes.com; +1 206-515-5631)

References

- Alaskan Way bored tunnel agreement – TunnelTalk, October 2009

- Seattle's bored tunnel - a story of politics – TunnelTalk, August 2011

- SR99 viaduct demolition next phase in Seattle – TunnelTalk, May 2018

- Appeal logged after jury finds for SR99 client – TunnelTalk, December 2019

- Tracking the world's mega-TBMs – TunnelTalk, March 2019

|

|

|

|

|

Add your comment

- Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts and comments. You share in the wider tunnelling community, so please keep your comments smart and civil. Don't attack other readers personally, and keep your language professional.