DigIndy progresses to final bore 10 Dec 2020

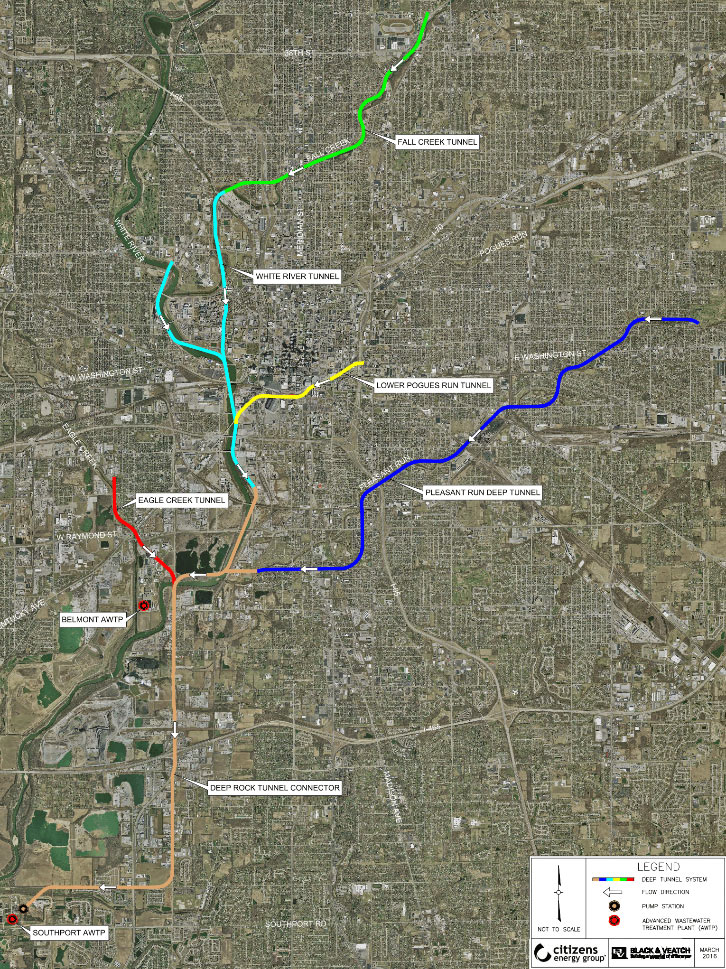

Excavation is now complete on all but one of the six deep CSO storage tunnels that form the DigIndy system in Indianapolis, USA, after the project TBM finished excavation of the 6.1km (3.8 mile) Fall Creek drive in April 2020 (Fig 1 and Table 1). The Robbins machine has now been retrieved by contractor JF Shea-Kiewit JV and transported to the launch site of the final 11.9km (7.4 mile) Pleasant Run drive, where it is being repaired and refurbished before relaunching in early 2021.

The total 45km x 5.5m i.d. (28 miles x 18ft) DigIndy network will intercept most of the 134 combined sewer overflows in the city and have a capacity of 1 million m3 (270 million gallons). Two sections, the Deep Rock connector and the Eagle Creek alignment, have been in operation since December 2017, capturing more than 7.6 million m3 (2 billion gallons) of overflow in that time.

Despite difficulties posed by control of the Covid-19 pandemic, the project remains on track to meet the 2025 completion deadline set by the USA Environmental Protection Agency, said Mike Miller, Construction Manager for owner, Citizens Energy Group. “We were slightly impacted, mostly by supply-chain issues early on in the pandemic,” explained Miller on a recent video call, “but overall, we are about where we expected to be.”

While there has been a supervising presence on site during the Covid-19 pandemic controls, Miller and his team have worked primarily from home since March 2020 and will continue to do so until at least February 2021. In that time, more than 250 site workers have safely kept the project moving.

Drill+blast adit and deaeration chamber excavation is now underway on Fall Creek, as well as continuing on the White River and Lower Pogues Run alignments. “Nine adits on Fall Creek total 1.7km (1 mile),” said Miller. “One is 500m long and expected to take five months to excavate.” Adits will be lined with precast concrete pipe, while the deaeration chambers will have a reinforced cast-in-place lining.

Unreinforced cast-in-place lining of the 9.3km White River and 2.9km Lower Pogues Run alignments is currently underway. According to the Federal mandate, the White River and Lower Pogues Run alignments are to be in service by the end of 2021, while Fall Creek and Pleasant Run must be operational by end 2025.

| Table 1. DigIndy construction phases | ||

| Alignment | Length | Status |

| Deep Rock Tunnel Connector |

12.2km (7.6 mile) | In service |

| Eagle Creek | 2.7km (1.7 mile) | In service |

| White River | 9.3km (5.8 mile) | Excavation completed April 2019 Lining underway |

| Lower Pogues Run | 3.1 km (1.9 mile) | Excavation completed Nov 2017 Lining underway |

| Fall Creek | 6.1km (3.8 mile) | Excavation completed April 2020 Lining to start mid 2021 |

| Pleasant Run | 11.9km (7.4 mile) | Excavation to start early 2021 |

Preparing for Pleasant Run

The same Robbins TBM has completed all drives of the project. For the final Pleasant Run alignment, the second longest after the Deep Rock connector, the machine cutterhead has been refurbished, a new main bearing installed, and the majority of the mechanical, electrical and hydraulic systems have been replaced. A large amount of the steel frame and decking also needed reinforcing or replacing.

TBM maintenance is to finish concurrently with construction of the Pleasant Run launch shaft and starter tunnel. Miller expects the machine to relaunch possibly as early as March 2021.

The launch shaft is located at the end of a spur excavated as part of the Deep Rock connector/Eagle Creek project. Two bulkheads, installed at the connection with Pleasant Run, allowed the Deep Rock/Eagle Creek phases into service ahead of Pleasant Run excavation. An opening cut through the upstream bulkhead and three valves installed through the second bulkhead allow for dewatering inflow during the Pleasant Run excavation directly into the Deep Rock connector.

Excavation of Pleasant Run is expected to take about 20 months with completion at the end of 2022/early 2023. Two additional large diameter shafts are being constructed on the alignment: an intermediary shaft at about the mid-point and a retrieval shaft about 1,000m from the tunnel end, which lies under a golf course. After reaching the end of the drive, the TBM will be backed up to the retrieval shaft for recovery.

Backing up of the TBM has been a feature of the project. It was backed-up after excavation of the Eagle Creek, Lower Pogues Run, western White River spur, and Fall Creek drives. “By the time we have finished, we will have backed up the machine along 9 miles – more than some projects go forward,” said Miller.

In addition to the deep tunnel network, about 6km (3.8 miles) of shallow sewers will be installed to consolidate the CSO points into eight drop shaft locations. Solicitation for the consolidation sewer work contract will occur in mid-2021 and work will progress concurrently with the Pleasant Run drive.

It is almost a decade since the Deep Rock tunnel connector was tendered by the City of Indianapolis in 2011. “The impact of this project,” said Miller, “will fundamentally change the condition of Indianapolis rivers and streams by capturing more than 97% of combined sewer overflows into these water bodies, all while remaining on schedule, under budget and with no violations of the consent decrees.”

References

- Challenges overcome as Kentucky CSO completes – TunnelTalk, October 2020

- Second of four main Tideway drives breakthrough – TunnelTalk, October 2020

- Cleveland progressing its CSO network – TunnelTalk, September 2020

- Potomac River CSO approved in Washington DC – TunnelTalk, April 2020

- Vice President speaks of DC Water Clean Rivers project – TunnelTalk, April 2020

- St Louis prepares fifth of eight CSO drives – TunnelTalk, January 2020

DigIndy TBM over halfway on 45km route 29 Aug 2019

Mining of the 6.1km (3.8 mile) Fall Creek section of the DigIndy deep-level CSO storage tunnel under Indianapolis is to begin in September 2019, following the completion of excavation on the White River route in April 2019, according to Mike Miller, Construction Manager for owner, Citizens Energy Group. About 27km (17 mile) of the 45km (28 mile) network has now been bored by a refurbished Robbins TBM that was previously used on the Second Avenue Subway in New York City, with the project on target to meet its Federally-mandated completion date of 2025.

The DigIndy project comprises six alignments. The 12.2km (7.6 mile) Deep Rock Tunnel Connector, DRTC, and 2.7km (1.7 mile) Eagle Creek elements have been operational since 29 December 2017, so far capturing 5.7 million meters3 (1.5 billion gallons) of CSO. Mining is complete on the 9.3km (5.8 mile) White River and 2.9km (1.8 mile) Lower Pogues Run sections. Lining work and adit/deaeration chamber construction is now underway on both.

Fall Creek will be the penultimate part to be excavated, after which the TBM will be refurbished and set to bore the 11.8km (7.3 mile) Pleasant Run alignment by contractor, a joint venture between Shea and Kiewit. The entire route is bored at a diameter of 6.2m (20ft) at a depth of 76.2m (250ft) with a 30cm (12in) cast-in-place concrete lining. When complete, the system will capture CSO from most of the 134 outflows in the city, holding about 1 million meter3 (250 million gallons) at any one time and preventing about 22.7 million meter3/year (6 billion gallons/year) of CSO flowing into the river.

Drive strategy

Despite the length of the DigIndy network, the project is using only one TBM and requires only eight large-diameter shafts, thanks to a drive strategy that has seen the machine mine three bifurcations to the main DTRC-White River-Fall Creek main alignment (Fig 1), before backing up and continuing. In contrast, the 41km main sewer in Abu Dhabi, which had an excavated diameter of 6.3m, used eight TBMs.

Earlier in the project, after mining the DRTC, the contractor proposed mining Eagle Creek, which was originally a shallow alignment, as a deep-level spur to the DRTC. This saved time and reduced surface disruption, while adding about 17 million gallons of storage capacity. To do so, the contractor backed the TBM down the DRTC, excavated Eagle Creek, then backed up again and walked the TBM to the end of the DRTC, avoiding the need for a retrieval shaft.

Mining on White River began in 2016. The machine bored north, up the White River alignment, before diverting east to excavate the Lower Pogues Run element of the project. It was then backed up and relaunched north, until diverting again to mine a northwestward spur of White River. The TBM was again backed up and relaunched to complete the main White River alignment. It is currently about 274m (900 ft) into the Fall Creek alignment, awaiting restart of excavation. When it reaches the end of Fall Creek, which Miller expects relatively quickly, in about March 2020, due to the favourable geology along that portion of the route, the TBM will be retrieved and refurbished. It will then mine Pleasant Run, which Miller expects to begin later in 2020.

“This drive strategy means we have only needed eight large diameter shafts,” said Miller. “Because we have been able to back up the TBM, the dead ends on Eagle Creek, Lower Pogues Run and the White River spur only required small-diameter shafts to allow flow down from the closest CSOs.”

The large diameter shafts are located at the Southport launch site, at the end of the DTRC, at the White River-Fall Creek boundary, and at the end of Fall Creek, as well as at the launch site, halfway up and about 914m (3000ft) from the end of Pleasant Run. “We were not able to put a large-diameter shaft where Pleasant Run terminates, so we are going to have to mine to the end of the alignment and then back the TBM up to the retrieval shaft.”

Groundwater infiltration during tunnel construction

For the most part, the geology has been fairly consistent limestone/dolomite bedrock, but some sections of higher groundwater infiltration have been encountered. As a risk mitigation measure, the owner and contractor worked together to develop a strategy for the implementation of probing ahead of the TBM face. If infiltration above a certain tolerance is encountered, the owner pays for the additional time and materials needed to resolve the issue. “This shared risk approach provides value to the owner based on expected levels of groundwater infiltration, but also protects the contractor should higher levels be encountered,” described Miller.

Pump station, ventilation and drop shafts

The project also included construction of a new underground pump station at the Southport treatment facility. Constructed by an Oscar Renda-Southland Contracting joint venture, it includes a 30m long x 18m wide x 23m high (100ft long x 60ft wide x 75ft high) cavern to house four 30 million gallon/day pumps. The cavern was constructed by drill+blast and is supported by 700 rock bolts. A waterproof membrane and then shotcrete finishes the cavern. The pump station is connected to the original launch shaft, which now functions as the screen and grit shaft, by a 1.8m diameter x 55 m long (6ft diameter x 180 ft) long tunnel.

Managing the ventilation was challenged by the various bifurcations along the route, explained Miller. “We do not want air from the mainline to enter the smaller runs because we only have a small diameter shaft at the end of those. So we have built 1.5m (5ft) diameter bulkheads from the crown to redirect any air and make sure it vents at the launch or retrieval shafts.”

There are 33 drop shafts along the route to bring surface discharges to the tunnel alignment with limited air entrainment. With the exception of those at the dead ends, these drop down into deaeration chambers that are connected to the mainline through adits. All of the adits and deaeration chambers are constructed by drill+blast, while the drop shafts themselves are primarily excavated by raise boring through the bedrock and by an innovative oscillation excavation method through the overburden.

“We have a mixed bag of overburden, as well as a high water table,” explained Miller. “This means we need a watertight retention system to be able to build the drop shafts through to the bedrock. To achieve this, we have used a crane-mounted rig that can take a 3cm thick x 3.7m diameter (1.25in thick x 12ft diameter) can and oscillate it through the overburden using a specialised clam bucket. It is a very efficient system: they can install two 30m-33m (100ft-110ft) shafts in less than two weeks.”

The efficiency of this system, combined with its rarity in the US, with only one or two in the country, prompted DigIndy to construct all the drop shaft overburden excavations at the same time, including those adjacent to sections that had not yet been excavated. “We have put all of the support of excavation cans in for the remainder of the program,” said Miller, completing the final one in late August 2019.

“DigIndy is one of the largest civil works projects in Indianapolis history,” Jeffrey Harrison, President and CEO of Citizens Energy Group, told TunnelTalk. “Citizens employees work hard every day to find innovative ways to keep DigIndy on schedule and below budget, and we are fortunate to have highly skilled contracting partners that continue to provide effective solutions to complex issues. When fully implemented, the DigIndy system is going to help restore water quality in local waterways to levels not seen in more than 100 years. The utilisation of our waterways as an asset to our community will improve the quality of life for central Indiana.”

References

- TBM launch for Indianapolis mega CSO project – TunnelTalk, October 2016

- Indianapolis awards 28km of deep-level tunnels – TunnelTalk, May 2016

- Rebuilt TBMs - are they as good as new? – TunnelTalk, May 2018

- Final push for cleaner waterway in DC – TunnelTalk, July 2018

- Breakthrough at Cleveland clean-up operation – TunnelTalk, April 2018

|

|

|

|

|

Add your comment

- Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts and comments. You share in the wider tunnelling community, so please keep your comments smart and civil. Don't attack other readers personally, and keep your language professional.