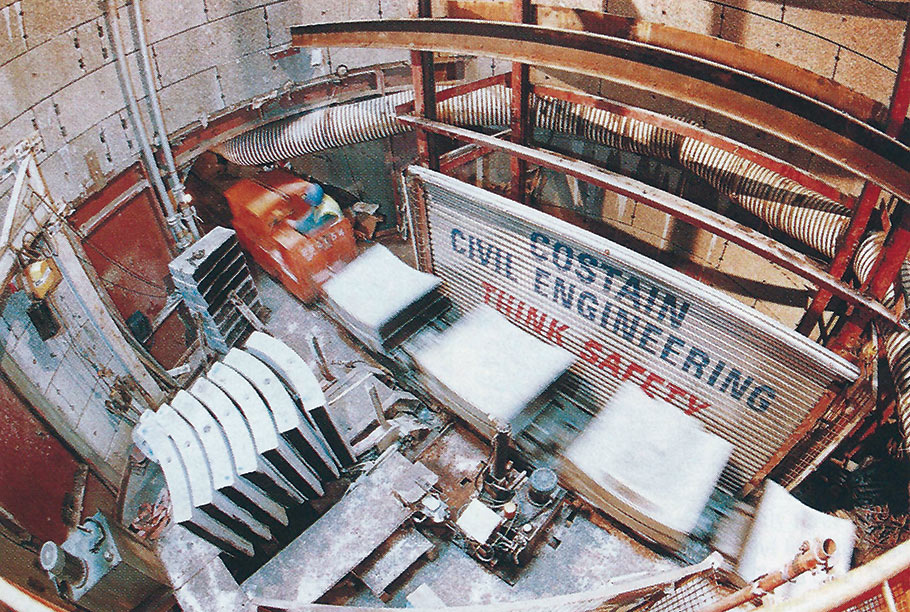

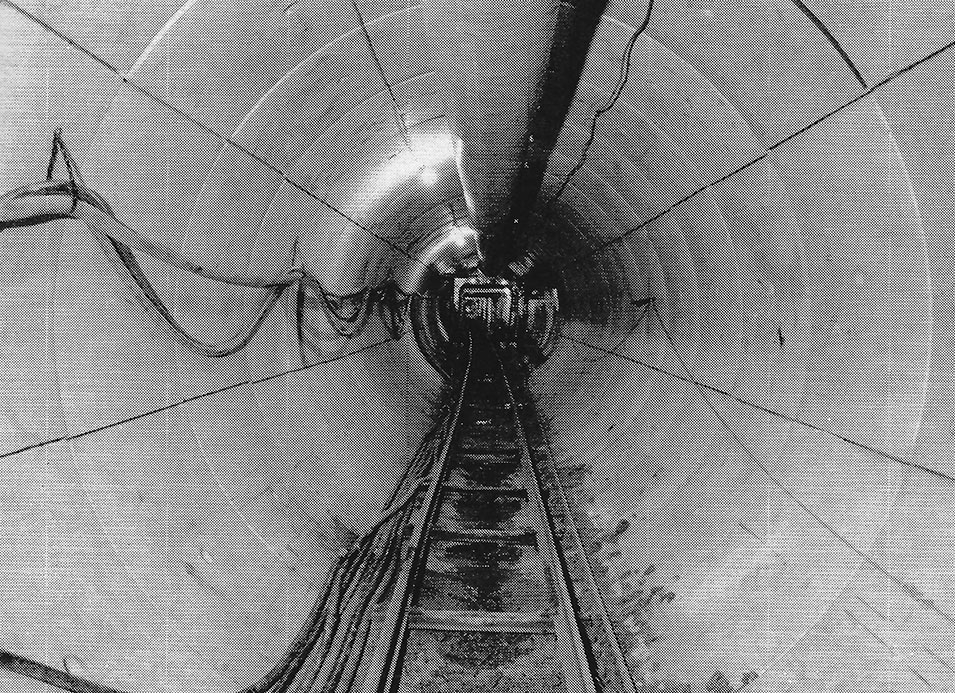

Efficient muck removal, mechanised segment handling, and a well organised routine by Costain has brought about safe, record time completion of the 7.8km long Moor Lane to Ashford Common connection as part of the London Water Ring Main strategy (Figs 1 and 2). Costain completed the 7.8km x 2.59m i.d. tunnel in two drives of 4.5km and 3.3km each. Despite these distances, average progress was 260m/week on the first drive and 300m on the second. All tunnel excavation was completed in nine months. As many as 51 rings of 1m wide x 180mm thick precast concrete wedge block segments were erected behind the Lovat TBM in a single 12hr shift. Best advance for a single 24hr day was 100m with 442m being the best advance for five non-consecutive working days or 10 shifts totalling 112 hours.

The tunnel runs an average 50m below the surface and entirely through Blue London Clay, a competent material that allows effective excavation by the Lovat machine and installation of the cost effective precast concrete wedge block segmental lining. Like all the current Ring Main contracts, the TBM and the segments for the lining are supplied by the client, Thames Water.

The Lovat TBMs are driven essentially by electrical and hydraulic motors and have an installed power capacity of 650hp with two 250hp motors driving the pumps for the cutterhead and one 125hp motor driving the pumps for the ancillary hydraulics including the muck conveyor. The TBMs came with a screw conveyor, muck ring, tail skin and triple tail seals for conversion of the tunnelling system to the bolted precast lining system should ground conditions deteriorate and prevent effective application of the expanded wedge block lining technique – a facility never needed on the Costain job.

Along with the TBM systems, Thames Water as the client, also provided to each contract all cables, hoses, consumables (including hydraulic oil and grease) and all necessary spare parts. As owner of the TBMs, Thames Water, in conjunction with Lovat, has specified a routine maintenance programme for all the machines. The hydraulic oil, supplied by Condat of France, is an environmentally safe, biodegradable, water-based product.

Under a £10 million contract with Thames Water, Taylor Woodrow supplied the segments of the precast concrete segmental lining for the last 33km of the Ring Main. For the most part, the wedge block lining is unreinforced, except for immediately adjacent to shafts. Designed to carry some 1,000 million litres of water/day with a gravity flow pressure of about 6 bar, the finished Ashford to Moor Lane tunnel will be tested to this standard for working pressure.

Unlike more traditional designs, the wedge block ring designed by Thames Water is wider, at 1m instead of 686mm, and has fewer segments per ring, eight instead of 12 including the key. This has contributed substantially to the increased progress rates being achieved. More than 1km of tunnelling has been completed by three Lovat machines for Thames Water in one week, an impressive achievement by any standards.

The new wider rings of segments have, however, created their own particular set of considerations. Perhaps most importantly, more unsupported ground must be exposed before the 1m wide ring can be erected. In good quality clay this is not a problem, but should the clay deteriorate or become blocky, problems can arise.

As this was the first of the three final sections of the Ring Main project to be let, Costain was involved in the design and specification of the Lovat TBMs procured by Thames Water. Recognising the potential problem of the length of exposed clay, Costain engineers recommended a set of seven 1.5m long x 10mm thick fingers on the back of the shields to provide partial support until the ring is built. A plough ahead of each finger cuts a channel to prevent them from becoming trapped behind the expanded ring.

The larger, heavier segments also require more mechanised handling. Segments are handled entirely mechanically from the delivery truck to installation at the tunnel face. At the pit bottom a mechanised automatic segment handler, designed jointly by Bennett Associates and Costain, lays the segments in correct ring build sequence on the bogies. In the tunnel, the integrated segment handling system, including the segment carrying bogies on the service trains, was designed jointly by Lovat and Thames Water. At the face, a mechanical handling system lifts the segments, turns them simultaneously into circular position, and moves them forward for lifting and placing by the Lovat erector arm.

A critical consideration when using the wedge block system of segmental lining is the exact cut diameter of the tunnel. The integrity of the wedge block system is derived from using the key for expanding the non-bolted segments out against the walls of the tunnel. Too large a cut diameter and the segments will not remain in stable compression. Too tight a cut diameter and the wedged key cannot be forced all the way into the ring. The actual size of the bead, or over cut, on the front end of the shield can only be determined once tunnelling is underway. On the Costain contract, it has taken several attempts to arrive at the correct overcut requirement. This exercise was exacerbated by using a long shielded TBM as opposed to an open-faced shield.

The Lovat machines are designed with all power packs in the shield rather than on trailing gantries. This leaves ample space in the back of the shield for segment handling and ring building, but it also results in a larger shield length-to-diameter ratio, compared to open-faced shields, which delays build of the lining at the end of each excavation stroke. In that time, the clay has sufficient time to begin its natural tendency to relax. This reduces the cut diameter of the tunnel making build of the wedge block lining more difficult.

Initially the 2,952mm diameter shield was supplied with a 17 piece x 6mm bead and a spare 12mm bead. "The front end of the shield is especially machined for the cutting bead to be attached by 51 cap-head screws," said Andrew Smith, Project Manager for Costain. "But even after fitting the 12mm bead, the cut was too tight. For correct ring build, keys had to be shortened while larger beads were manufactured. Squeezing in of the clay, coupled with the length of the TBM, required a 33mm bead," said Smith. "After fitting the 33mm bead, no further problems were experienced with driving the keys home at the correct pressure."

The clay on the second drive was poorer than on the first according to Smith. "It has a higher moisture content at 22% as opposed to 17% or so. It is also very fissured and blocky at this depth of 45m of 50m below the surface. The softer clay tends to ball up in the excavation chamber slowing progress and the softer crown will squeeze on. Also, the slick sided clay blocks will drop from the crown."

During the site visit, the TBM had almost finished the second drive and had been standing at full stroke for an hour or so for a minor repair. In that time, blocks in the crown of the exposed clay had dislodged proving the worth of the trailing fingers on the shield.

The Costain schedule for the contract is calculated on a 15 min/1m cycle. It was actually achieving an average of about 12 min/cycle with 6 min to excavate a 1m stroke and 4 min to build a ring.

Interruptions in the muck hauling cycle, connecting new lengths of cable and ventilation duct, and other routine stoppages account for the remainder. "Our estimated long average was for 200m/week working two 12hr production shifts Monday to Thursday, with two 8hr shifts on Friday", said Smith. "We have actually achieved a production average of 300m/wk including driving curves of 800m and 1,200m radius and maximum 600m in length requiring frequent repositioning of the laser and prism beam deflectors."

The muck hauling system, always a significant factor in production rates, is based on trains of 7 x 2m3 side tipping skips from Decon, hauled to the shaft bottom by 5 tonne Clayton electric locos. Each train carries the 13m3 of muck/1m ring (about 7.25m3 solid) while the locos are supplied with high capacity batteries which allow a maximum 42km between charges for the given drawbar pull and gradient.

During construction, the single haulage track was divided every 800m with a switch. Towards the end of the first longer drive, seven muck trains and four switches were in service and trains were programmed to travel between crossings in 6 min. For safety's sake, the 40m-long trains were always pulled, never pushed. As such, the locos changed ends on a switch towed behind the TBM and another at the shaft bottom.

At the shaft, the side tipping skips are emptied individually into a 20 tonne hopper which is lifted to the surface for onward muck disposal. Two tower cranes service the working shaft. One 30 tonne unit is dedicated to the muck hopper giving a turn round in the 50m deep working shafts of about 6 min. The second smaller 12 tonne crane lowers segments and supplies.

The three 50m deep shafts on the contract 10.3m i.d., 9m i.d. and 12.5m id.. They will ultimately house large diameter steel connecting pipe work and high integrity valves. The shafts were sunk as caissons with steel cutting edges through the 6-8m of flood plain gravel at the surface, and underpinned to full depth using precast concrete segments supplied by Charcon with some from C V Buchan, all to Thames Water's order.

The 400mm ventilation ducting, supplied by Flexadux, is paid out in 200m lengths from cassettes on the TBM trailing gantries. A rigid GRP duct in a flat oblong shape of equivalent cross section allowed safe passage of the filled skips at the slightly elevated crossings. Muck in the skips was levelled automatically before leaving the TBM.

Given the long distances between relatively deep shafts and the high level of activity from shaft top to tunnel face, safety is a major consideration. As such, and in conjunction with Thames Water, Costain has produced a site-specific safety manual. All employees, including management, are acquainted with the safety procedures described in the manual, and regular induction and refresher sessions remind all of safe working practices as well as correct emergency procedures.

Because employees and tunnelling crews must be constantly aware of the underground working environment or near shafts, special attention is paid to safe means of entry to, and exit from, all confined spaces. Gas monitoring is undertaken as a routine procedure and anyone entering the tunnel carries a self-rescuer and an identity tag. Key personnel, such as crane drivers and banksmen, are only appointed once they have demonstrated a competency in all safety procedures and, where required, can produce the necessary registration certificate.

In the event of a major incident, the site is well prepared. A well equipped rescue bogie, designed specially by Costain, stands on a siding in the pit bottom ready at all time for immediate use. It has space for a stretcher and medical attendant and is equipped with a comprehensive first aid kit, resuscitation equipment and multiple breathing sets using umbilical hoses. In addition, Costain has arranged with the nearby Ashford Hospital to utilise its emergency rescue service. Known as BASICS (the Berkshire and Surrey Immediate Care Service), this provides a fully equipped doctor to an accident or emergency site within 15 min.

The fact that no accidents of a serious nature have occurred on the contract to date is witness to the emphasis that Costain and Thames Water place on safety and is a credit to the working routine established by Costain on a tunnelling job where such high advance rates have been achieved.

Similar to the other Ring Main contracts for Thames Water, Costain is completing its almost 8km long contract as a design-construct target cost contract based on the I.Chem.E. Green Book form of contracts. As Costain's engaged designer, Charles Haswell & Partners completed the detail design not only of the tunnel but also of all the complex connection into the Ashford treatment plant and the Wraysbury reservoir. It also completed the site investigation study. This included bore holes every 200m to 5m below tunnel invert to confirm the predominance of London Clay at tunnel alignment. A number of shorter interim holes were sunk to determine the upper gravel/clay interface and to identify, if possible, the presence of scour holes, a potential anomaly at the outer edges of the London Clay basin.

After launching the Lovat TBM in July 1991, the final breakthrough occurred in early May 1992. After completing the finishing works, Costain expects to hand over the finished job on schedule in June 1993.

Top quality projects with clean safety records such as this, elevate tunnelling from a perceived dangerous occupation to a dedicated trade and profession, undertaken by informed and safety conscious employees.

|

|

|

|

|