TBM remanufacturing to meet eco targets June 2019

As politicians grapple with the challenges of climate change and the transition to a low carbon economy, former Davy Markham Managing Director, Bill Clark, argues that the TBM manufacturing industry needs urgently to re-think its approach to procurement, design and machine lifecycle if it is to comply with ever more stringent legislation and make the most of the emerging remanufacturing market.

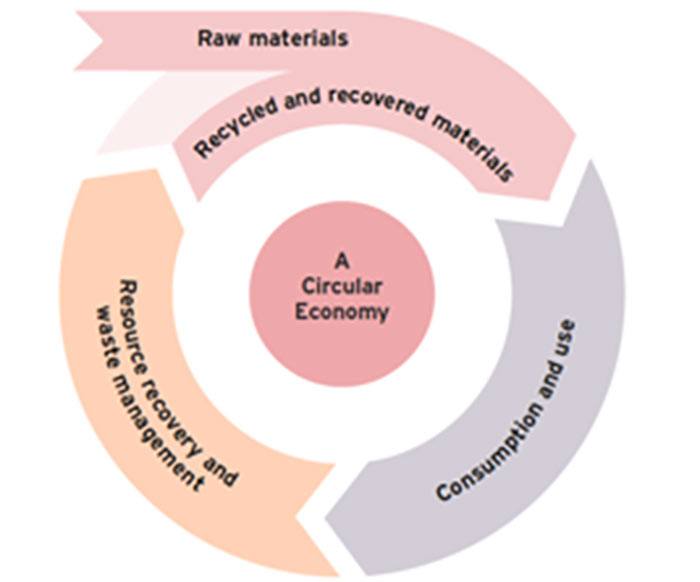

Strategy for sustainable production Source: UK Government report Our Waste, Our Resources: A Strategy For England

The 25 Year Environment Plan announced recently in the UK sets minimum requirements through eco-design to encourage resource-efficient product design. Likewise, in the EU, member countries have voted to include eco-design requirements in product regulation for resource efficiency, taking into account the potential to design for machine disassembly, repair and recyclability. This approach has been strengthened through the UK Industrial Strategy, while the Procuring for Growth Balanced Scorecard ensures major government infrastructure procurements include environmental impacts and benefits. This means that for the future procurement cannot be awarded on price alone.

In a paper by the Carbon Trust entitled Supporting Excellence in UK Remanufacturing, the cost of remanufacturing is stated as between 40% and 65% of new components and uses 85% less energy than when newly manufactured. The remanufacturing industry – where parts or products at the end of their useful life are returned to like-new or better condition – could be worth more than £5 billion to the UK alone and could reduce carbon by millions of tonnes worldwide.

TBM specifications and procurement have traditionally been driven by price, reliability, buy-back and programme. This has created relatively narrow global supply chains which are rarely assessed against sustainability or environmental benchmarks. This has led to the use of low-cost /high CO2 steel produced via basic oxygen coke-fired blast furnaces. The procurement process is further compromised through ignoring in-country legislative commitment to recycling, waste minimisation, renewable energy and CO2 reduction targets.

Scrap steel is an important part of the raw material feedstock. In China the shortage of scrap, combined with its relatively low price, has led to increased use of basic raw materials and a proportionally higher CO2 footprint / tonne of steel produced. In addition, China has recently decided to ban the import of low-grade steel and this will compound the CO2 footprint problem in the short term.

In addition to resource inefficient manufacturing processes, the transportation of TBM components, often weighing many hundreds of tonnes, from one side of the world to the other results in hundreds of tonnes of shipping carbon. The Carbon Trust has flagged the need to procure steel from lower CO2 sites and arguably this should be extended to include embodied carbon in final traded goods.

The buy-back of TBMs encourages the reuse of plant and equipment. In 2019 the ITAtech committee of the ITA (International Tunnelling and Underground Space Association) updated its 2015 Guidelines on rebuilds of machinery for mechanized tunnel excavation report which includes the refurbishment and re-engineering of TBMs. Herrenknecht and the The Robbins Company both ensure they retain comprehensive inventories of refurbished or re-engineered components. However, some client specifiers are following a policy of precluding the incorporation of used components in machines for their projects due to concerns over history, life expectancy, inadequate quality assurance documentation, or deficient maintenance records.

ITAtech guidelines for TBM rebuilds

Download the 2019 Guidelines on Rebuilds of Machinery

While not directly comparable with TBMs, the UK rail industry has been carefully maintaining traction and rolling stock for many years. In some cases vehicles are more than 50 years old and are operating reliably in what is a safety critical environment.

The big differentiators are:

- Components are designed to operate for many operational cycles

- The equipment maintainers are formally trained and are of high competence

- OEM maintenance procedures are followed and comprehensive maintenance records retained

- Design and equipment data sheets are up to date

- Operational hours are logged

As environmental legislation and regulation is tightened to drive a more efficient and sustainable use of scarce resources, it is evident that the industry needs to rethink the way TBMs are specified, designed, manufactured, maintained, operated and re-engineered. Greater attention must be given to the CO2 footprint during the phases of procurement, operations and recovery if the TBM industry is to make a meaningful contribution to decarbonisation. No longer should the industry be allowed to wait for someone else to take the lead. Surely we have to be bolder, confront the decarbonisation challenge, learn from others and provide best practice guidance to TBM specifiers, designers, remanufacturers and operators.

If we do not embrace the environmental and sustainability challenges, we may find that tough legislation is forced on us. We will also have to live with the fact that we know we could and should have done better.

References

- Rebuilt TBMs - are they as good as new? – TunnelTalk, May 2018

- Refurbished Mixshield sets a fast pace in The Hague – TunnelTalk, May 2019

- Time for UK politics to get boring – TunnelTalk, May 2019

- ITAtech Guidelines on Rebuilds of Machinery for Mechanised Tunnel Machinery -

Download the pdf report

|

|

|

|

|

Add your comment

- Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts and comments. You share in the wider tunnelling community, so please keep your comments smart and civil. Don't attack other readers personally, and keep your language professional.