An early Chinese TBM experience at Qinling Jan 2000

The potential market in China is a strong attraction for western TBM manufacturers. China has well-established experience in drill+blast but its immediate need is for the latest TBM technology. China is attempting to acquire within a few years the know-how that Europe, the USA and Japan have developed over several decades, and the need for China is urgent for development of road, rail, metro, water supply, water power and sewerage projects. China also has ambitions of becoming a serious competitor in the international tunnelling industry, and to meet these goals, it realises that it must buy the expertise, at least initially. One of the latest companies to enter TBM co-operation with China is Wirth GmbH of Germany.

First contact with the Chinese for Wirth came in 1994 when an invitation to fill an enormous order for two TBMs came from the China National Technology Import Corporation (CNTIC), the organisation that handles all import agreements with international organisations. The client in China would be the national Ministry of Railways (MoR) and the initial project would be excavation of an 18.5km long tunnel through the Qinling Mountains on the new US$1.2 billion electrified railway between Xi'an and Ankang in central China. The two required TBMs would be 8.8m in diameter and capable of boring through hard to very hard granite and gneiss.

In addition to the two TBMs, the Chinese purchased all the back-up equipment including drill rigs, steel arch ring erectors, shotcrete systems, grout mixers and injection pumps, together with full sets of muck wagons, rotor dumpers, locos, ventilation equipment. The order was also to include training courses in Europe, on-site technical assistance, consumable and spare parts supply, and civil engineering advice and assistance during the initial phase of the drives.

Two 8.8m diameter hard rock TBMs, together with all associated backup and support equipment, were supplied by Wirth of Germany to the 18.5km long Qinling railway tunnel

The Wirth supply order included:

- 72 x 20m3 Mühlhäuser muck cars plus a total 32 units of remixers, manriders and segment cars

- 10 x 45 tonne and 35 tonne diesel locomotives from Schöma

- ventilation fans

- shotcreting systems from Putzmeister

- grouting equipment from Häny

- Tamrock probe and rockbolting drill rigs

- invert segment moulds

- full scale trailing back-up systems designed by Wirth and manufactured in collaboration with Wirth Howden in Scotland, subcontractor Rowa in Switzerland, and by Chinese manufacturing company Baogi

- a contract for supply of consumables and spare parts including oils, grease and cutters, and

- a machine service and operator training agreement.

Along with Wirth, the invitation to bid went to the top hard rock TBM manufacturers including The Robbins Company which had just been taken over by Atlas Copco of Sweden. Robbins delivered its first tunnelling machines to China in 1984, two rebuilt 10.8m diameter Chicago TARP machines for a hydro project, and delivered six more of smaller diameter, three of which were working in the late 1990s.

For Wirth this would be the first association with mainland China in tunnel boring, although it had been dealing with China on different mining projects for some time and had already delivered two 11.74m diameter machines to Taiwan for the Pinglin highway tunnel project. Final negotiations for the Qinling order was between Robbins and Wirth as two of the world's most experienced hard rock TBM suppliers.

For Qinling the MoR awarded TBM tunnel project to two of its construction bureaus. The two TBMs would work from the opposite portals towards a midtunnel breakthrough. From the North Portal, located about an hour-and-a-half drive from Xi'an, one TBM would be operated by TEB, the Tunnel Engineering Bureau of MoR's China Railway Engineering Corporation (CREC). From the South Portal, at the end of a more difficult three-hour drive over two high mountain passes, the TBM work was awarded to the 18th Construction Bureau of the China Railway Construction Corporation (CRCC).

Together with the TBM drives, MoR and its design engineer, the Number 1 Survey and Design Institute of Railways in the city of Lanzhou, adopted a parallel pilot tunnel heading to investigate rock conditions and provide access for pre-treating anticipated fault zones and areas of poor rock on the TBM alignment. The pilot tunnel, which will be enlarged to accommodate a future doubling of the new line, is smaller than the main TBM tunnel at 30m2 and was driven by drill+blast. Work on the pilot started from both ends in January 1995, with the 1st Construction Bureau working both the pilot and the TBM headings at the South Portal, while at the North Portal a third contractor, MoR's 1st Construction Bureau, was responsible for the pilot bore. TEB, as main contractor for the TBM tunnel at the North Portal, also had overall responsibility for the project TBM operations. Supervision of both the drill+blast and the TBM tunnels was in the hands of the South West Research Institute of China's Academy of Railway Sciences based in Chengdu.

After the final period of extremely tough and competitive negotiations, the final decision between the Wirth and the Robbins bids eventually came down in favour of Wirth in April 1996 and in October 1996 an order worth Japanese ¥6.4 billion (DM95 million) was signed between Wirth and the Import Corporation. The order was placed in Japanese Yen because the project is supported financially by the Japanese overseas Economic Co-operation Fund. According to Wirth, the six months between selection and signing was spent refining technical specifications and defining the volume of cutters and cutter parts for the whole project.

As part of the order negotiations, the TBMs were designed to achieve an average advance of 1km in three months, giving the project a boring programme of approximately 27 months. MoR's programme for the new 264km long railway, with about 130km running through 90 tunnels, was to have it in operation by 2001. With the TBMs ordered in October 1996 and taking eight to nine months to manufacture before being shipped to China, the Qinling tunnel was always to be the critical element on the line. But still, with good planning, good management and a generous dose of good luck, the TBMs could meet the programme. In June 1997, both machines were shipped from Antwerp. They arrived on site in August and September 1997 and after about three months in assembly they were launched in January and February 1998 at the North and South Portals respectively. After the calculated 27 month boring programme, breakthrough at the mid-point could be expected during Spring 2000.

Learning curve hurdles

While relationships between the customers and the supplier have grown positive with time, the road to TBM breakthrough was a challenging and often frustrating experience for both sides. An understandable difficulty was the language barrier. The common language between the Germans, the Swiss, and the Chinese, both in the contract documents and on site, was English. While most of the senior Chinese engineers and managers speak good English, communication in English was mostly via two official interpreters engaged at the two portal headings who worked hard and were conscious of their responsibilities. The process of sharing knowledge and experience also required development of additional skills in diplomacy, cross cultural tolerance and patient understanding on both sides.

“The contract with our Chinese customers brought us into the closest association we have ever had with a client,” said Norbert Kamin, Project Manager for the Qinling project for Wirth. This technical co-operation started with training courses. More than 100 Chinese engineers lived in Europe for up to three months each, working both in the Wirth factory and the design department at Erkelenz during manufacture of the machines, and on the Vereina railway tunnel project in Switzerland where they acquired first-hand experience of operating a Wirth hard rock TBM. In fact, it was on the Vereina project that the Chinese based many of their TBM expectations, from potential TBM progress rates to management of consumables and spare parts, and management of the rock support requirements.

Transfer of this experience from the trained members of the Chinese team back to the engineers, technicians and operatives back on the project in China was a complex task, assisted on-site by Wirth technicians and Amberg Consulting engineers from Switzerland. After working on the Vereina project, Amberg joined the Qinling order package to provide civil engineering advice and assistance on the large diameter hard rock TBM headings.

“According to the terms of the contract, our site responsibility was to manage and supervise assembly of the TBMs and then to manage and supervise their operation over the first 1km commissioning period,” said Kamin. “Following that, we were to hand over the full day-to-day operation, maintenance and management of the machines to the Chinese crews and provide technical assistance when called upon to do so. The Amberg engineers were engaged for the first 1km, a period of about three months, and returned to Europe after handing over the full civil engineering responsibilities to the design and supervising engineers.”

In the field, communication across the cultural divide was a further challenge. Different attitudes between the two cultures regarding the care and maintenance of tools, equipment and machinery also had to be conveyed and usually most effectively via example. However, it was difficult on occasions to find the source of recurring problems to instruct or correct misunderstandings.

Practical experience

Once the Chinese crews took over the daily operation of the tunnelling work, some maintenance routines, particularly on service equipment, suffered. In one instance, the compressed air emergency break systems on the trains of ten 20m3 Mühlhäuser rotor dump cars soon became faulty and were disconnected. The danger of the situation was demonstrated when a loaded muck train uncoupled from the loco and careered back down the downhill heading into the back of the TBM. Fortunately, nobody was injured. Following the accident, the emergency brake systems on the muck trains at both portals were rehabilitated.

The rock was generally massive and favourable for TBM excavation, but rock falls and rock burst were frequent due the high in-situ stresses beneath the maximum 1,600m, and average 1,000m, mountainous overburden. Support compising ring beams, rock bolts, wire mesh and shotcrete could be installed immediately behind the cutterhead but this would cause TBM downtime if extensive. Support was therefore often delayed until the area was beneath the secondary support station approximately 30m back on the trailing gantries, where support could be installed concurrent with TBM boring. By that time however, the rock, depending on its condition, had deteriorated further. On one occasion, a large rock fell from the crown damaging a rock bolting rig and TBM working platforms.

At 30m from the face, it can also be difficult to expand ring beams tightly against the relaxed rock causing further instability. Several methods were used to try and resist the movement, such as welding rods of rebar between the sets or between rock bolt breast plates. This resulted in several tight spots along the tunnel where arches had to be cut back to allow the operator cabin on the top deck of the trailing backup to pass though.

North Portal TBM utilisation in March 1999 (left) when start of bearing seal replacement accounted for the 68% standstill and in August 1999 (right) when a daily best of 40.6m was recorded

Introducing themselves to the sophisticated technology of the PLC (programmable logic control) system of the TBM was also a complex task that led to events of computer software malfunction during the learning curve.

Managing cutter consumption was an overall serious cause of concern. The most damage occurred when replacement of the centre cutter was delayed. Boring continued until the entire six-disc unit had been ground flat, with the cutterhead breast plate leaving a 300mm dumpling of hard rock in the face.

Along with the standard warranties on the equipment, Wirth had undertaken a standard cutter consumption guarantee within certain rock strengths and conditions. While the quality of the granite and gneiss at Qinling is not overly abrasive, it is very hard at between 117 and 192MPa, and average 150MPa on average, for the granite and between 129 and 325MPa (average 250MPa) for the harder compound gneiss. Consumption in the granite was generally lower than anticipated at about 9 to 10m/disc ring average, while in the gneiss it was much higher than expected at about 1.6m/ring. Higher than expected consumption can also be attributed to ring breakages caused by blocky rock and flat spots caused by either oil leakages from the disc bearing or other reasons for preventing the discs from turning.

At Qinling, the number of cutters used on each TBM was almost the same, but the number of disc units discarded by each portal operation differed widely. The cutter workshop and recycling system established and operated by Professor Wan on the South Portal achieved high utility with a disc bearing life of up to 500 hours and a recycling record of up to 11 reuses. This is beyond manufacturer estimates or recommendations. Cutter salvage at the North Portal fell short of the impressive South Portal record.

Much of the higher than expected wear in the gneiss was also attributable, Wirth believes, to excessively high compressive strengths - higher than the maximum 325MPa value set down in the contract documents - as well as to cutting through very hard dolerite dyke intrusions and to coping with extremely high insitu stresses of the maximum 1,600m overburden. No core samples were taken from the tunnel face where actual in-situ stresses are best tested, but tunnel boring records give some indication of the rock strengths. In some cases, it took up to, and sometimes more than, 6 hours to cut a 1.8m stroke. The Wirth discs are rated for a recommended loading of 250kN each, giving a recommended cutterhead thrust of about 17,000kN. The machines are driven by eight two-speed electric motors, at speeds of 2.7 or 5.4 rev/min, and the breakout torque is 8.7kNm. An auxiliary hydraulic motor attached to each electric motor gearbox allowed breakout torque to increase to a maximum of 10.5kNm and while this facility has only rarely been engaged, forward thrust has often exceeded 18,000kN in efforts to penetrate the rock and achieve advance.

Such high in-situ stresses, and consequent high machine thrust forces, are also suspected of having contributed to development of cracks in the internal support ribs and muck chute scrapper blades on the TBM cutterheads. These were welded on various occasions and braces were introduced to strengthen the ribs. This improved the situation and while cracks continued to be present, they did not propagate and were repaired by Wirth once the TBMs were removed from the tunnel and as part of the warranty agreement.

Cracking occurred on both machines and more seriously on the North Portal machine. Welding of the cracks took place on a set of two or three occasions. One of these took place at the same time as a one-month downtime on each machine to remove, modify and replace all the gear box units. These were found to have a manufacturer-defective sur-clip and all were rectified by Wirth in a single operation rather than as they failed.

Another two-week period of TBM downtime in March/April 1999, 14 months after starting, was required to replace a failed main bearing seal on the North Portal machine. This was replaced by Wirth at its own expense and as part of the warranty agreement, but the root cause of the failure was undetected.

Other points of concern, itemised as open points by the Chinese TBM owners and operators, had to be clarified and rectified before acceptance notices for both machines were signed in June 1999.

Progress to early finish

During the drives, achieving advance was the top priority. The North Portal TBM started boring in medium strength granite in January 1998 and the South Portal started a month later in very hard gneiss. The best rate of penetration for both machines was in the granite with an average of 150MPa, in which the 1.8m stroke was cut in a best time of 25 min. The slowest rate of penetration was 6 hours to cut a stroke in hard gneiss of up to 325MPa. The norm was 50-60 min/stroke with the TBM operating at about 16,000kN thrust and about 2,500kNm torque.

Cutter wear was a recurring concern. “Average wear in the granite was about 9.5m/ring and about 1.6m/ring in the gneiss,” explained Sha Mingyuan, Project Manager at the South Portal. “About 95% of the cutter consumption on our operation is wear of the rings and about 5% is breakages or bearing seal oil leaks or other reasons. The first set of centre cutters on our TBM lasted 2,085m starting in the very hard gneiss.”

Both Sha and Francis Liu Jun, Project Manager for the North Portal operation, confirmed that availability of the TBMs ran as high as 90-95% but that utilisation in a 24hr day (boring time + gripper resetting time) ran at less than 30% on average. A large portion of the downtime was for cutter inspection and changes with maintenance of the TBM and the backup system accounting for another large portion.

Despite averaging 338.7m/month on the South Portal and about 265m/month on the North Portal, including the threemonth downtime for mechanical repairs, the TBMs were not destined to make a face-to-face breakthrough as originally planned. At some stage, it was decided that excavation of the Qinling tunnel would be one of the major civil engineering projects selected to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the 1949 foundation of the People's Republic of China. Excavation of 18.5km of 8.8m diameter hard rock tunnel by 1 October 1999 was well ahead of the original 27-month TBM programme and was achieved only by excavating the central 5km section by drill+blast, using the completed parallel pilot tunnel as access.

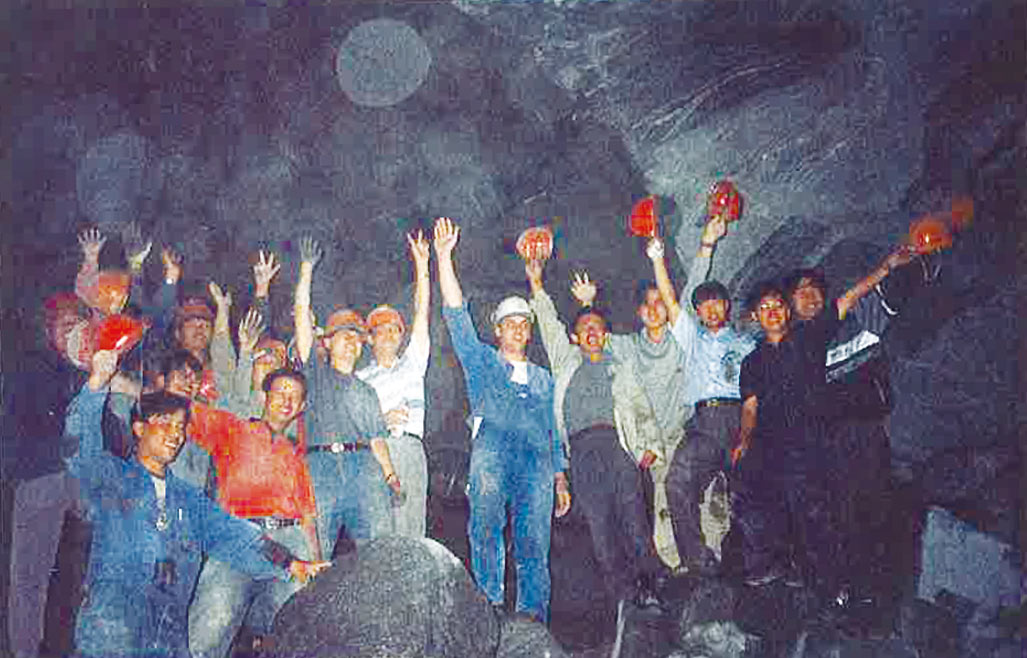

Drill+blast excavation of the pilot started in January 1995 and was completed in March 1998. During its excavation, suspected sections of poor rock on the main tunnel alignment were excavated by drill+blast with the TBMs pulled through the drill+blast-excavated zones. Excavation of the 5km long central section of the main tunnel by drill+blast is believed to have started in September 1997, well before the TBMs were launched in January and February 1998. As a result, the two TBMs completed 5,621m from the South Portal and 5,255m from the North Portal, breaking through into chambers at the end of the central drill+blast section. These breakthroughs occurred on 21 and 29 August respectively, well in time for the PRC foundation day celebrations.

While the combination was vital to meet the 1 October 1999 deadline, it also presented an opportunity to compare the differences between the TBM and the drill+blast operations. Comparisons are always difficult to quantify, regarding exactly what is included and what is excluded, however, Liu at the North Portal explained that if 100% represents the cost of the TBM tunnel excavation, the drill+blast excavation of the same size tunnel through the same rock accounted for 30% of that. That is less than half as expensive. “However, this comparison was made at a time during the first year when we had a lot of problems with the TBMs and very high cutter costs,” said Liu. “The second year, when many of these problems were rectified, the TBM costs in relation to the same drill+blast costs reduced to about 75% of the previous year's 100%.” The full cost of the Qinling tunnel, including the final 300mm in-situ concrete lining of the main tunnel and excavation of the drill+blast pilot tunnel, is believed to be about RMB2 billion or about US$241 million.

Regarding time, drill+blast in the central section averaged about 400m/month but this, it was said, was achieved working three faces at once using the two hydraulic Atlas Copco jumbos at two of the headings and hand-held equipment at the third.

Given all the information and the project history, the Chinese were asked if the TBM experience was considered successful. “In the beginning, when we were experiencing very difficult problems, most considered the use of TBM technology on this project was wrong,” said Liu. “Now, most senior people in the MoR think that TBM excavation was right."

At the South Portal, when asked, Sha said that “the TBM is a very effective tool for tunnelling. It has higher speeds than drill+blast; it is safer than drill+blast; and concrete consumption for the secondary lining is much less.” Regarding operation of the TBM he said, “the technical side is more strict, the technology is more complicated than drill+blast, but the operation is more convenient with high automation which is easily controlled.” Concerning cost he said that the cost of spare parts and cutters, which are imported from overseas, contribute to the higher cost. This will be addressed no doubt by China's commitment to being able to manufacture the spare parts, components and disc cutters to the necessary standard and quality in the near future. China made its first attempt to duplicate a Robbins hard rock TBM in the early 1970s and Professor Wan, Manager of the South Portal disc cutter workshop, was engaged on that project as the disc cutter expert. That particular project proved unsuccessful but the aspiration to develop its own hard rock TBM technology is much revived in China and a text book publishing the technical details and specifications of the Wirth TBMs employed at Qinling was produced for circulation in China.

In the shorter term, and with the knowledge and experience gained at Qinling, the two MoR construction companies engaged are bidding on several overseas jobs in South East Asia as skilled and experienced labour subcontractors including on the deep sewer tunnels in Singapore. It will be very difficult for others to beat the cost of Chinese labour and with the leap forward gained by the Qinling experience, the two companies have a fair chance of winning such sub-contracts.

Meanwhile, the two Qinling TBMs are to move directly to their next job. This is believed to be a 19km long railway tunnel on the new Xi'an-Nanging electrified railway. That tunnel is some 25km from the Qinling one and passes through the same mountain range. Following breakthrough of the TBMs in August 1999, Wirth technicians were on site to assist with the dismantling and refurbishment of the machines. The machines are expected to be ready for re-assembly on the new tunnel sites in early 2000.

As a closing statement from Wirth, Norbert Kamin said: “Qinling has been interesting and challenging. This is the first time we have worked with mainland China in a tunnel project; it is the first time we have been responsible for supplying the entire TBM tunnelling package; and the machines were designed, built and equipped to the highest available specifications to cope with very demanding rock conditions. There were mechanical problems that we had to resolve and several troubleshooting problems to rectify. The project has been a major learning experience for both parties and is regarded by both sides as a successful implementation of TBMs in hard rock. We very much look forward to continuing our association and co-operation with Chinese clients and wish them every success in their move towards modern, high quality and efficient TBM tunnelling.”

Eventually, in 2013, the intellectual property and TBM manufacturing business of Wirth in Germany was purchased by the CRTE China Railway Tunnelling Equipment company which is part of the China Railway Engineering Corporation and owner of TEB, Tunnel Engineering Bureau, that operated the North Portal TBM and was responsible for the overall TBM operations at Qinling. CREG Wirth is now a well-established international TBM manufacturer and supplier.

Acknowledgements

- Thanks are extended to the Qinling job site personnel and to the Wirth engineers for supporting the job site visit in August 1999 and for informative discussions.

References

- TBMs engaged for rail project at Qinling – TunnelTalk, May 1998

- CRTE of China takes over Wirth TBM business – TunnelTalk, November 2013

- Vereina railway shot cut in Switzerland – TunnelTalk, February 1993

- Alpine baseline railway tribulations in Switzerland – TunnelTalk, May 1997

- Record-setting TBM headway under high overburden in China – TunnelTalk, July 2011

- Record setting TBMs on Yellow River drives in China – TunnelTalk, January 2001

- Visit our Archive and use our TunnelTalk search facility for a wealth of information about tunnelling and underground engineering projects in China.

|

|

|

|

|

Add your comment

- Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts and comments. You share in the wider tunnelling community, so please keep your comments smart and civil. Don't attack other readers personally, and keep your language professional.