America's high speed rail aspirations

Sep 2006

By Paula Wallis, Reporter

-

Fig 1. 11 HSR corridors eligible for federal funding

- More than four decades after the US Congress pass the High Speed Ground Transportation Act (1965), true high-speed train travel remains an illusive goal. Political will, lack of funding, and powerful opposing interests have, or threaten to derail several ambitious regional plans.

- Florida's high-speed rail (HSR) project is going nowhere fast. In 2004 voters repealed an earlier amendment to the state's constitution mandating the construction of a HSR system. Governor Jeb Bush led the charge, citing flaws in the plan and threats to nearly $17 billion in road projects. Under the plan, bullet trains would link the five largest urban areas in Florida, with the first phase running between Tampa and Orlando (Fig 2). The project has been in limbo for the last two years for want of funding.

- California's HSR plans seem destine for a similar fate. After more than 10 years of planning, the first phase of California's High Speed Rail (HSR) system was set to begin next year. But the dream of bullet trains shooting between San Francisco and Los Angels, in less than three hours, is now on life support.

-

Fig 2. Florida's planned high speed rail

- "The legislature is in a complete jumble at the moment on high speed rail. No one wants to carry the torch for this project," says Alan C. Miller, Executive Director of the Train Riders Association of California. "The project needs a champion, like the Governor."

- But that's not likely. Governor Schwarzenegger's proposed 10-year, $222 billion public works spending plan unveiled in January 2006 doesn't include a single penny for HSR, and the legislature, struggling to fund more pressing public works projects, may pull a $9.95 billion bond measure for HSR off this November's ballot.

- The rail bond would help pay for the first leg of the multi-billion system that has trains whisking passengers between San Francisco and Los Angeles in as little as two and a half hours. Eventually the 700-mile, $37 billion dollar project would link San Francisco, Sacramento, Fresno, Los Angeles and San Diego (Fig 3).

- Numerous tunnels are called for along the route, including the underground extension into the new Transbay Terminal in San Francisco.

- The design team for this section includes Parsons Brinkerhoff, Arup and Jacobs Associates.Two alignment alternatives are being considered and the Second-to-Main Street option is preferred. As planned, the tracks would descend into a tunnel near Berry Street, curve east and continue on under Townsend where they will curve north at

-

Fig 3. California's high speed rail route

- Third Street, continue under Second to Howard and curve into the new terminal. A combination of open-cut, cut-and-cover and bored tunneling methods will be employed (Fig 4). The overall length of the of the mined tunnel section will vary depending on geological conditions along the alignment, but is expected to be about 3,000ft long.

- No preferred route is identified for the north mountain crossing from the Bay Area to the Merced region.

- The broad alignment corridor contains a number of feasible options all of which will include tunneling.

- One of the greatest construction challenges will be the south mountain crossing from Bakersfield to Los Angeles. Two viable options are being considered, but the preferred route follows Interstate 5 highway over the Tehachapi Mountains and will include 28 miles of tunnels (Fig 5). The other option is 41 miles longer but includes only 11 miles of tunnels. Based on engineering results and other data the preferred route is expected to cost about $700 million less to build and would produce higher annual ridership and lower operating costs.

-

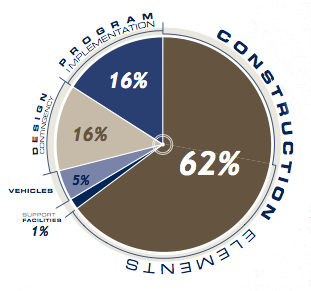

High speed rail costs

It is estimated that construction of the high speed rail line will account for 62% of the capital costs with 25% of that going to structures, tunnels and walls (Fig 5). Champions of HSR warn that without an initial investment, the project might never get build. Detractors prefer funding-fixes for existing congestion rather than gambling finite dollars on HSR.

-

Fig 4. Underground extension into the new Transbay Terminal

- In an attempt to keep the project alive Senate President Pro Tem Don Perata, D-Alameda, has included $1 billion for HSR in a public works bond that would repeal and replace the original $9.5 billion HSR bond. It will be used to purchase right of way and grade separation. Still Perata is less than optimistic that even this amount will survive the political haggling over how much and what bonds are likely to get passed by the voters. He recently summed up the attitude in Sacramento: "In a world of finite choices, when you combine what you know you need and haven't done, with what the public wants done, high-speed rail sounds too futuristic and does not generate the kind of enthusiasm any number of other projects do."

- That appears to be the prevailing attitude in Washington also. HSR has received little support from the Federal Government. In 2004 the Federal Government invested less than $600 million on rail infrastructure, while spending $30 billion on highways and $24 billion on aviation.

- Amtrak, the nation's passenger rail service, has limped along losing money and suffering under inadequate funding from Congress since it was founded in 1970. The Bush Administration, which had zero funding for Amtrak in its 2006 budget, has earmarked $900 million for the railway in fiscal 2007. The administration is calling for reform of Amtrak, with a shared role for federal and state governments in owning and maintaining the infrastructure, with private-sector competition providing service. Describing the administration's plans in a recent speech, Transportation Secretary Norman Y. Mineta said: "We are willing to put taxpayer money to fund passenger rail where it makes sense, but we aren't where it doesn't." Privatization of the rails has taken hold in countries around the world. The UK's switch in the 1980s is held up as a model for success.

- Other nations are investing heavily in HSR. China is pumping $80 billion into expanding its system and in January, Mexico opened bidding on a $12 billion, 180mph 'Tren Bala' or bullet train, that will run 360 miles between Mexico City and Guadalajara, the country's second-largest city.

- Despite the current political climate in the US, public support for HSR is gathering steam. Thirty-six states around the nation have HSR projects on the drawing boards and the federal government has designated 11 high-speed rail corridors around the nation, making them eligible for federal funding (Fig 1).

Fig 5. Cost breakdowns: capital costs (left); construction costs (center); operation and maintenance (right)

- Rising oil prices, and increasing traffic and air congestion are fueling the public cry for alternatives. According to a 2005 study by the Texas Transportation Institute, traffic congestion is costing Americans $63.1 billion a year. California's population is expected to grow from 35 million to 48 million over the next 25 years. Without high speed rail supporters say the state would need to build 30 new airline gates, five new runways and 3,000 new miles of highway with an estimated cost of $87 billion, to accommodate that growth. By comparison, $37 billion for HSR is a bargain!

-

California to bring high speed rail to North America - Video - TunnelCast, Nov 2008

California fixes high-speed rail route - TunnelTalk, Jul 2008

Austria: Design considerations for high-speed rail - TunnelTalk, Feb 2008

California High Speed Rail plans - Video - TunnelCast, Nov 2008

Feedback - TunnelTalk -

USA Federal High Speed Rail Corridors

California High Speed Rail Authority

Transbay Terminal

Amtrak

Mexico High Speed Rail