Hawk's Nest Tunnel tragedy

Sep 2009

Betty Dotson-Lewis, Contributor

-

Seven decades later, the State of West Virginia, remembers the more than 400 workers who died in the building of the 3.8 mile Hawk's Nest Tunnel. Last month the West Virginia State Humanities Council awarded a grant for the building of a memorial to the workers. Local writer Betty Dotson-Lewis takes a look back at the tragedy.

-

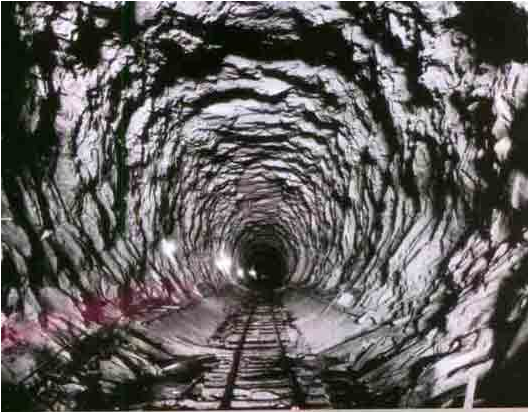

Worker emerging from Tunnel

- Owen Symes, made a soft, deliberate roll with his right hand as if he were directing a top-notch orchestra. He told me:

- "I used to rabbit hunt over there on the Martha White farm out in the fields before Rt. 19 came through here. I could see the graves. They were little soft mounds of dirt with grass over them. If you were not careful, you could step on one and it would cave in. They were in rows right up and down the fence line. They moved a lot of them when the highway came through. Dug up the graves and took what was left down by Hughes Bridge on the Gauley River to bury them again."

- Owen was talking about the graves of black migrant workers - victims of the Hawk's Nest Tunnel disaster. Nobody knows for sure how many people died; 760 is the number you hear. Nobody knows for sure how many were buried on the Martha White Farm and other places in Nicholas County.

- Details of the Hawk's Nest Tunnel tragedy, considered to be the nation's worst industrial disaster, have successfully been kept under wraps for years, but now that Union Carbide has moved on, people feel they can at last talk about the horrible details of this shameful time.

- During the 1930s Depression, men were desperate for work of any kind. When word got out that there were jobs in the West Virginia hills, hundreds of black migrant workers from the Deep South hopped trains and rode north to the coal mining fields. But the jobs were not mining coal. Instead, a company needed workers to drill a tunnel through Gauley Mountain, located between Ansted and Gauley Bridge in Fayette County, West Virginia.

- The 3.8-mile Hawk's Nest Tunnel was an engineering marvel. The tunnel's purpose was to divert water from the New River through the Gauley Mountain and down a drop of 162 feet to provide electricity to the Electro Metallurgical Company, a subsidiary of the Union Carbide Corporation.

- Construction of the tunnel began in June 1930. Workers moved forward from 250 to 300ft per week through 99.44% pure silica, 32-36ft in diameter. Experts knew that miners who inhaled silica dust would contract silicosis, a deadly lung ailment. But the company ordered that the workers use a dry drilling technique that would create more dust because this method was faster and cheaper.

-

Excerpt from 1979 Federal OSHA

film, 'Can't Take No More'The Rinehart & Dennis Company from Charlottesville, Virginia, was awarded the two-year contract from Union Carbide for construction of the tunnel. Engineers from Union Carbide were in charge of overseeing the operation.- Of the hundreds of people employed, at least two-thirds of the workers were African-American migrants. The black diggers emerged from the hole in the mountain covered with clouds of white dust - ghostly. The interior of the tunnel was a white cloud of silica, impairing vision as well as clogging the lungs.

Many accidents crippled or killed workers before the silicosis could choke them to death. Masks were supplied only to inspectors and company men inside the tunnel.- Workers began dying two months after they first entered the tunnel.

- Of the hundreds of people employed, at least two-thirds of the workers were African-American migrants. The black diggers emerged from the hole in the mountain covered with clouds of white dust - ghostly. The interior of the tunnel was a white cloud of silica, impairing vision as well as clogging the lungs.

- The deaths were painful, as the silica they inhaled created extensive and fibrous nodules on the lungs. Their lungs grew stiff. The men found it harder to breathe and, ultimately, they strangled to death. It was reported that Cecil Jones struggled so hard for his breath that he kicked the wooden slats out of the baseboard of his bed before he died. Silicosis cannot be cured. A company doctor told the tunnel workers they had a new disease called, "tunnelitis" and gave them worthless pills.

- On May 20, 1931, the local newspaper, The Fayette Tribune, broke the story, telling about the sick and dying tunnel workers and their inhumane and unsafe working conditions, but a gag order issued by a local judge stopped publication.

- Living conditions were deplorable. Workers were housed in 8ft x 10ft overcrowded, segregated boxcars in Vanetta, a small community outside Gauley Bridge. They also lived in Gauley Bridge, a small town that became known as "The Town of the Living Dead." A Congressional report from February 4, 1936, described the scene: "The men got down so they had no flesh left on them at all. As they express it down there, the men got so they were all hide, bone and leaders, which means he is just skin and tendons and looks like a living skeleton."

-

The tunnel was through silica

- Many of the 5,000 who worked the tunnel died from silicosis after they retuned home. Or, they lived but suffered. Arthur Stull of Mt. Lookout, West Virginia, lived to the age of 87, but his daughter, Phyllis Stull Arms, told me every breath he drew was painful.

- Directly, a problem arose as black workers died. There was no "colored" burial site. Handley White, local funeral parlor owner in Summersville, located a field on his mother's farm and was given a contract to open a burial ground on the Martha White farm in Summersville. Handley was paid $50 per body with the promise of "plenty of business."

- Lieber Cutlp, a local resident, remembered the time well. Lieber was a good friend of one of Handley's sons, and he had the fortune of owning a flatbed truck. Handley's son asked Lieber if he wanted to make a little extra money using his truck for a hauling job. Lieber, anxious to make a little extra money, agreed.

- The dead workers were stacked in rows and strapped on the back of the flatbed truck. More of the dead black workers were put in an upright sitting position as if they were alive for their ride to their final resting place. For years rumors spread about workers buried in mass graves on the Martha White farm, but White family members deny this accusation.

- I had the opportunity to speak with H. C. White, another son of Handley's and current owner of the local funeral parlor in Summersville, when I began working on this story. He told me another burial site was behind the Presbyterian Church, in close proximity to the property now owned by Charlotte Yeager-Neilan. When I asked Mr. White why the workers were not returned home to their families for a proper burial, he said, "No one knew where to send the bodies."

-

Existing memorial

- Jennings Randolph of West Virginia sat on a Senate subcommittee that investigated the disaster in 1936. Reports from the subcommittee vigorously spoke out against the conditions at Hawk's Nest, but that was the extent of action taken. The tunnel was completed and has performed its purpose ever since. Silicosis has been designated as an occupational disease with compensation for workers because of the Hawk's Nest disaster, however, tunnel workers were not protected by these laws.

- Charlotte Yeager-Neilan, publisher of the Nicholas Chronicle, discovered evidence of graves on the hillside behind her house in Summersville. Rocks were the only markers. Yeager-Neilan felt that a memorial to honor the victims would indicate to families that even though seven decades have passed, the town was not without pity.

- In August of 2009, The West Virginia State Humanities Council awarded a $10,000 grant to construct a memorial to the Hawk's Nest Tunnel victims who were buried in Summersville and surrounding Nicholas County.

Gordon Revey, P.Eng.

Kudos to Tunnel Talk and the author of the Hawk's Nest Tunnel Tragedy Article. Modern miners often forget how many lives were lost during the dark times of lax and/or criminal neglect regarding environmental and workplace safety in underground excavations.